When we look out at the Universe today, we see that it’s full of stars and galaxies, in all directions and at all locations in space. The Universe isn’t static, though; the distant galaxies are bound together in groups and clusters, with those groups and clusters speeding away from one another as part of the expanding Universe. As the Universe expands, it gets not only sparser, but cooler, as the individual photons shift to redder wavelengths as they travel through space.

But this means if we look back in time, the Universe was not only denser, but also hotter. If we go all the way back to the earliest moments where this description applies, to the first moments of the Big Bang, we come to the Universe as it was at its absolute hottest. Here’s what it was like to live back then.

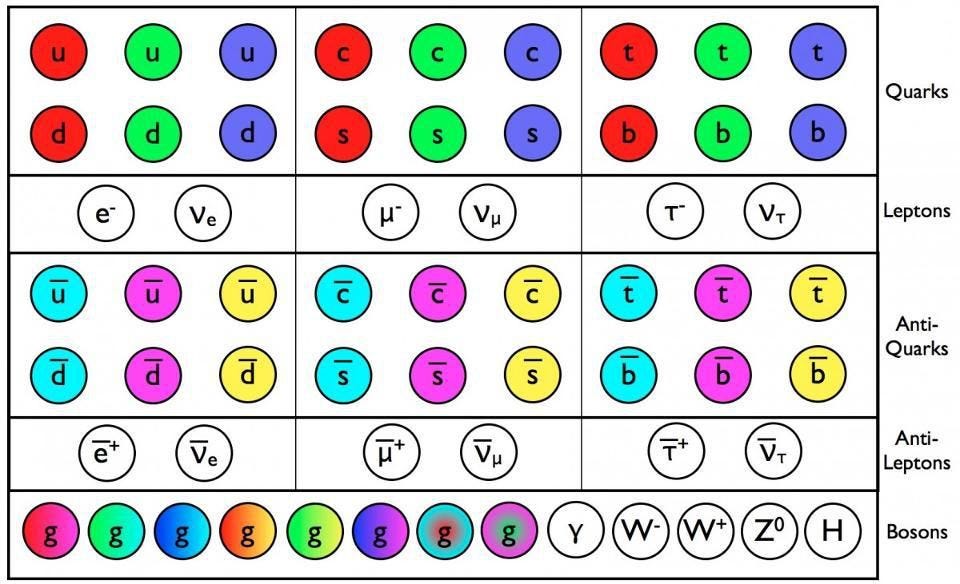

In today’s Universe, particles obey certain rules. Most of them have masses, corresponding to the total amount of internal energy inherent to that particle’s existence. They can either be matter (for the Fermions), antimatter (for the anti-Fermions), or neither (for the bosons). Some of the particles are massless, which demands they move at the speed of light.

Whenever corresponding matter/antimatter pairs collide with one another, they can spontaneously annihilate, generally producing two massless photons. And when you smash together any two particles at all with large enough amounts of energy, there’s a chance that you can spontaneously create new matter/antimatter particle pairs. So long as there’s enough energy, according to Einstein’s E = mc², we can turn energy into matter, and vice versa.

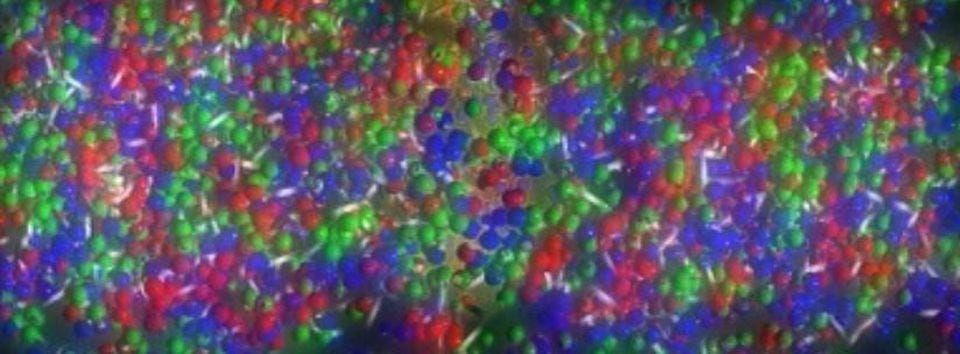

Well, things sure were different early on! At the extremely high energies we find in the earliest stages of the Big Bang, every particle in the Standard Model was massless. The Higgs symmetry, which gives particles masses when it breaks, is completely restored at these temperatures. It’s too hot not only to form atoms and bound atomic nuclei, but even individual protons and neutrons are impossible; the Universe is a hot, dense plasma filled with all the particles and antiparticles that can exist.

Energies are so high that even the most ghostly known particles and antiparticles of all, neutrinos and antineutrinos, smash into other particles more frequently than at any other time. Every particle smacks into another countless trillions of times per microsecond, all moving at the speed of light.

In addition to the particles we know, there may well be additional particles (and antiparticles) that we don’t know about today. The Universe was far hotter and more energetic — a million times greater than the highest-energy cosmic rays and trillions of times stronger than the LHC’s energies — than anything we can view on Earth. If there are additional particles to produce in the Universe, including:

- supersymmetric particles,

- particles predicted by Grand Unified Theories,

- particles accessible via large or warped extra dimensions,

- smaller particles that make up the ones we now think are fundamental,

- heavy, right-handed neutrinos,

- or a great variety of dark matter candidate particles,

the young, post-Big Bang Universe would have created them.

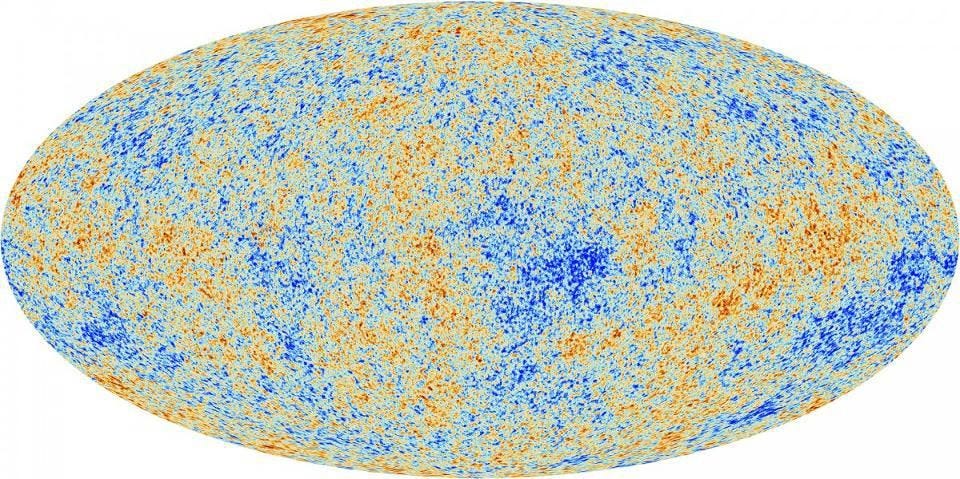

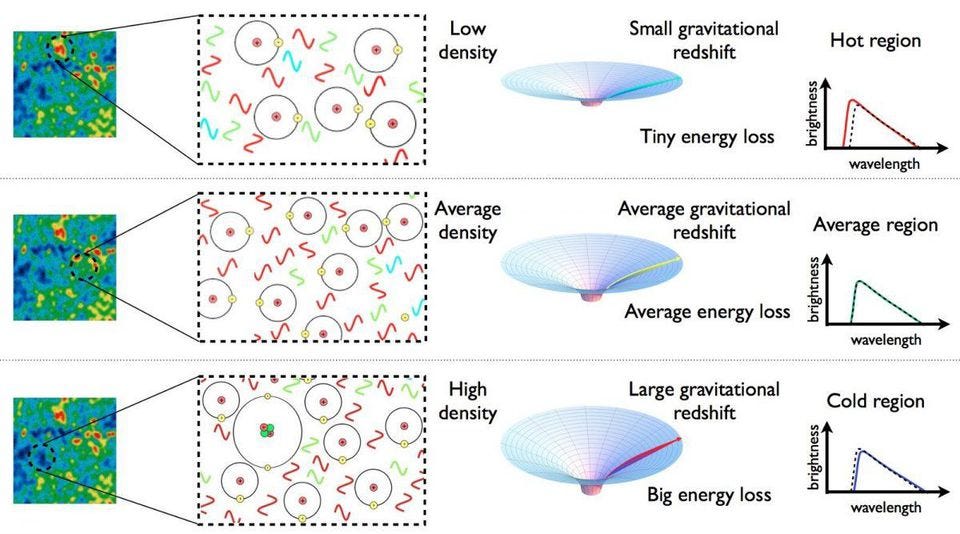

What’s remarkable is that despite these incredible energies and densities, there’s a limit. The Universe never was arbitrarily hot and dense, and we have the observational evidence to prove it. Today, we can observe the Cosmic Microwave Background: the leftover glow of radiation from the Big Bang. While this is a uniform 2.725 K everywhere and in all directions, there are tiny fluctuations in it: fluctuations of only tens or hundreds of microkelvin. Thanks to the Planck satellite, we’ve mapped this out to extraordinary precision, with an angular resolution that goes down to just 0.07 degrees.

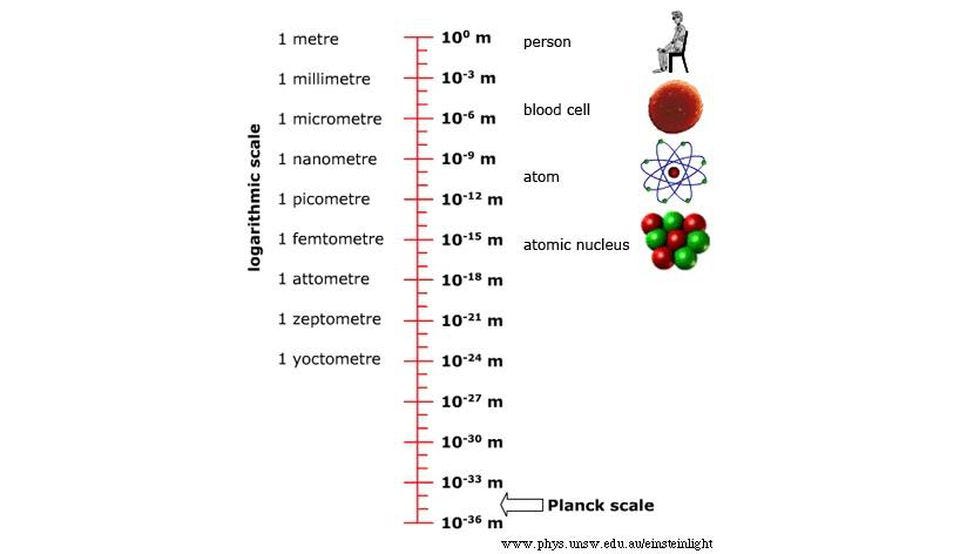

The spectrum and magnitude of these fluctuations teaches us something about the maximum temperature the Universe could have achieved during the earliest, hottest stages of the Big Bang: it has an upper limit. In physics, the highest possible energies of all are at the Planck scale, which is around 10¹⁹ GeV, where a GeV is the energy required to accelerate one electron to a potential of one billion volts. Beyond those energies, the laws of physics no longer make sense.

But given the map of the fluctuations we have in the Cosmic Microwave Background, we can conclude those temperatures were never achieved. The maximum temperature that our Universe ever could have achieved, as shown by the fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background, is only ~10¹⁶ GeV, or a factor of 1,000 smaller than the Planck scale. The Universe, in other words, had a maximum temperature it could have reached, and it’s significantly lower than the Planck scale.

These fluctuations do more than tell us about the highest temperature the hot Big Bang achieved; they tell us what seeds were planted in the Universe to grow into the cosmic structure we have today.

The cold spots are cold because the light has a slightly greater gravitational potential well to climb out of, corresponding to a region of greater-than-average density. The hot spots, correspondingly, come from regions with below-average densities. Over time, the cold spots will grow into galaxies, groups and clusters of galaxies, and will help form the great cosmic web. The hot spots, on the other hand, will give up their matter to the denser regions, becoming great cosmic voids over billions of years. The seeds for structure were there from the Big Bang’s earliest, hottest stages.

What’s more is that once you reach the maximum temperature achievable in the early Universe, it immediately begins to plummet. Just like a balloon expands when you fill it with hot air, because the molecules have lots of energy and push out against the balloon walls, the fabric of space expands when you fill it with hot particles, antiparticles, and radiation.

And whenever the Universe expands, it also cools. Radiation, remember, has its energy proportional to its wavelength: the amount of distance it takes a wave to complete one oscillation. As the fabric of space stretches, the wavelength stretches too, bringing that radiation to lower and lower energies. Lower energies correspond to lower temperatures, and hence the Universe gets not only less dense, but less hot, too, as time goes on.

At the inception of the hot Big Bang, the Universe reaches its hottest, densest state, and is filled with matter, antimatter, and radiation. The imperfections in the Universe — nearly perfectly uniform but with inhomogeneities of 1-part-in-30,000 — tell us how hot it could have gotten, and also provide the seeds from which the large-scale structure of the Universe will grow. Immediately, the Universe begins expanding and cooling, becoming less hot and less dense, and making it more difficult to create anything requiring a large store of energy. E = mc² means that without enough energy, you can’t create a particle of a given mass.

Over time, the expanding and cooling Universe will drive an enormous number of changes. But for one brief moment, everything was symmetric, and as energetic as possible. Somehow, over time, these initial conditions created the entire Universe.